|

Die Glasstraße

Author: Uwe Rosenberg

Publisher: Feuerland Spiele

Year: 2013

review by

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For many centuries, Bavaria has been one of Europe’s leading glass manufacturing centres. There is a 250km long ‘Crystal Road’ with glassware manufacturing facilities open for public, where visitors can see the glass in all stages of production. In Die Glasstraße we re-live the golden era of glass production: in four periods we build all kinds of buildings, using sand, clay, loam, wood, and of course home-made glass.

|

|

|

|

|

| xx |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

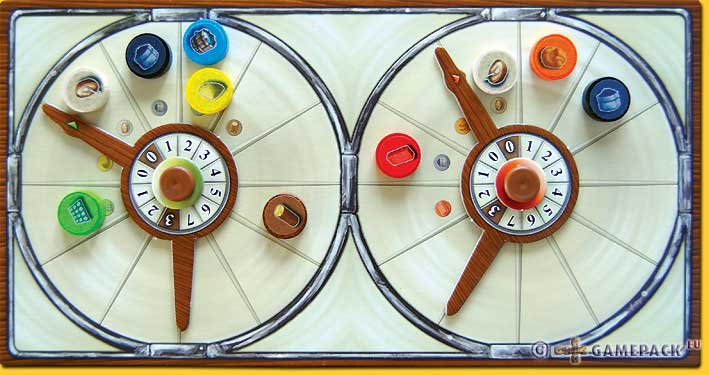

The game is equipped with no less than two rondels per player; the rondels are used to keep track of how many resources the players possess. Each rondel has two hands, set at ‘8 o’clock’; in the largest area the simple resources are collected, indicated by wooden discs. The smaller area contains one complex resource: glass in the first, and brick in the second rondel. Whenever a player collects a resource, he moves the corresponding disc in clock-wise direction. As soon as the hands are able to move in clock-wise direction (because the positions on the right-hand side of the hands are empty) this automatically happens: the number next to the complex resource disc has now increased by 1, while the numbers corresponding to the simple resources have all decreased by 1. In fact, this means that one of each simple resource has been used to produce one complex resource.

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

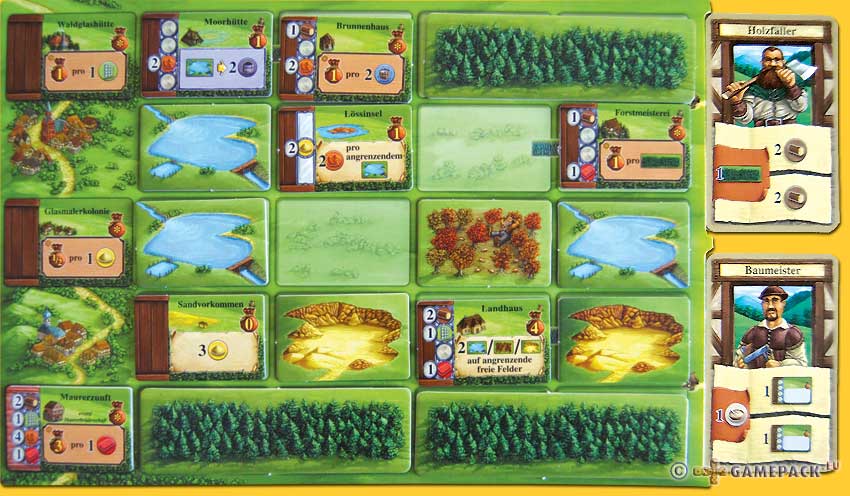

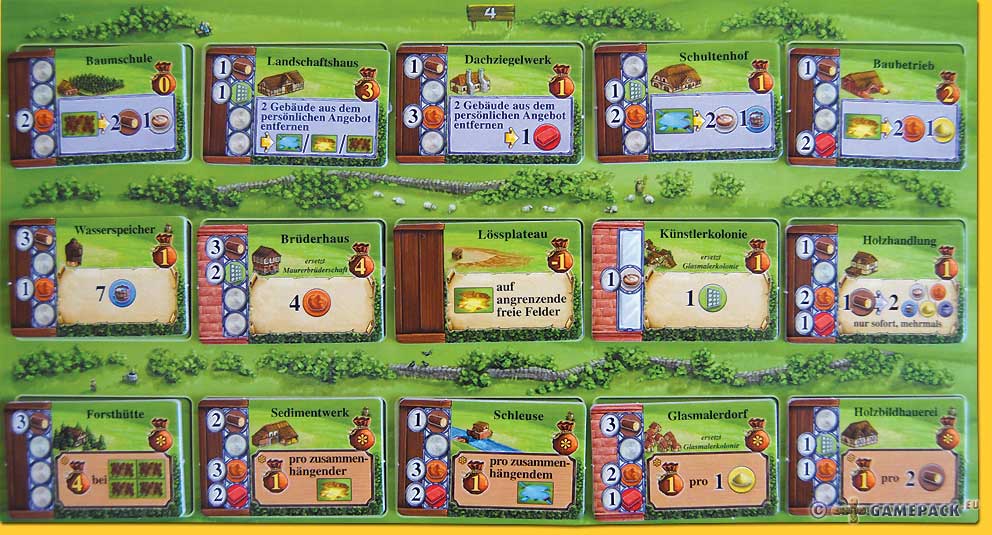

| Whenever a player has to pay a resource, usually to pay for the construction of a building, the corresponding disc is moved to a lower number. There are three types of buildings in the game. A production building can be used by its owner to convert something into something else. The sofort-buildings usually produce something the moment they are built, but they’re pretty useless after that. The victory point buildings yield points at the end of the game, when certain conditions are met. The buildings are constructed on the player’s own player board. There is some available space, but also woods and some other landscape tiles that have to be removed before a building can be placed there. |

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

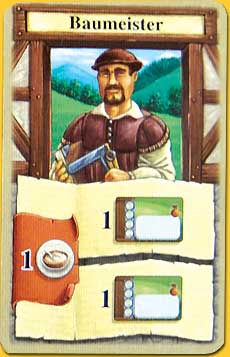

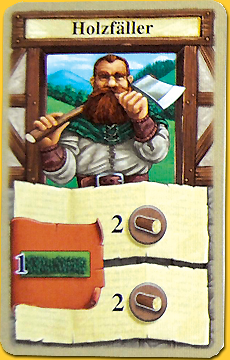

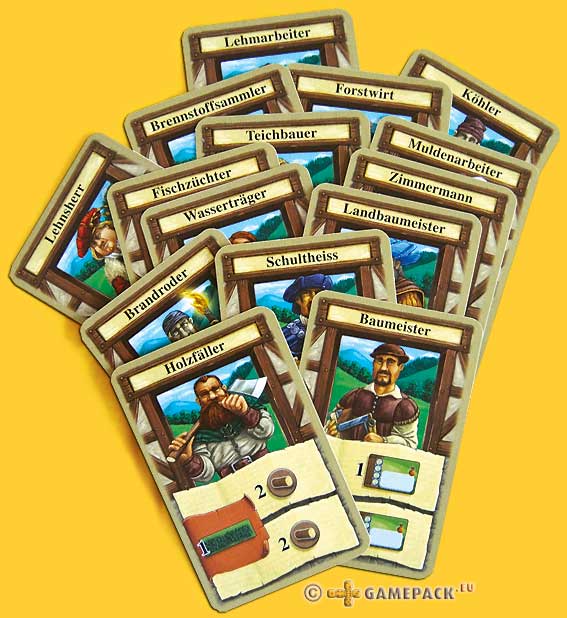

| Each player has a set of 15 cards. These are the characters that can be used to perform actions. The most important action is to construct a building: no buildings, no glory. But buildings have to be constructed from something, so there are also cards to collect resources. A specified number of specified resources, or a resource of your choice, or as many resources of a specific kind as you have landscape tiles of a specific type on your player board. Placing landscape tiles is also one of the possible actions, or cutting down forest tiles. |

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Each building period consists of three rounds. At the beginning of each period, the players select five cards from their hand. Of these five cards, everybody chooses one card he’d like to play first; this card is placed face-down. The starting player opens his face-down card. If any of the other players has this exact same card still in his hand (not face-down in front of him!), he has to show the card. Then, the starting player performs one of the two actions depicted on the card, followed by the other players with this same card. But if there were no other players with the same card, he may perform both of the depicted actions! After that, the next player takes his turn by showing his face-down card, et cetera. Because there are only three rounds, each player can play only three of his five selected cards, performing one or both actions on this card. But it is also possible to play the remaining two cards as well, because another player played this card while you still had it in your hand. After four building periods the game is over. Players collect points for buildings, and additional points for meeting specific requirements depicted on some of the buildings. For example, two points per adjacent water tile, or one point per sand (resource) remaining on the player’s rondel. |

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

| x |

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Buildings score victory points. The essence of the game is to build as many of them as possible. That takes time, actions and resources. It is therefore favourable to be able to carry out as many actions as possible. And there we immediately run into the biggest disadvantage of the game. In the most favourable scenario, a player is able to play three cards for two actions each, and two more cards for one action each, so eight actions in total. But in the worst case scenario the player has no unique cards, and is allowed to use only one action from all of his three cards, and he doesn’t get the opportunity to play his remaining two cards at all: three actions in total. That is a very big difference. You would therefore expect that players have some influence on how many actions they are able to perform, but that turns out not to be the case. A game like Citadels (Ohne Furcht und Adel) has eight very distinct character cards, and therefore some educated guessing / philosophical contemplating is possible : ‘John desperately wants to construct a building, he is very likely to choose the Architect’. But not in Die Glasstraße. John would like to construct a building? There are four characters that allow such an action. He seems tob e in desperate need of some wood? Six different character cards can help him out. And so on. This way, it is impossible to guess which cards your opponents have selected, even if you know which actions they would like to take. And it is even more impossible to guess in which order they will play the cards! So it’s about 100% coincidence whether you end up performing only three, or as much as eight actions in any given round. |

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The gimmick with the rondels also doesn’t work out as it should. As soon as the hands turn, they immediately do. Whether it suits you or not. That would be acceptable if you had some sort of influence over the cards you play and the order in which you play them, but as indicated before, that is not the case. It happens all too often that you have exactly the four required clay for the building you would like to construct. You play your Architect card face-down, all ready for action! But then, an opponent plays a card that you also have in your hand, and you are forced to play it. This card causes you to receive a resource, the disc moves, the rondel moves and… now you have only three clay left!! Of course you may refuse to perform an action, but chances are that this other card was also part of your master plan, and if you’d refuse to perform the action, other parts of the plan will come crashing down… If something like that happens once, you grind your teeth and bravely continue. But Die Glasstraße is one concatenation of such frustrating events. Many of the available actions cost one resource. But with all this (often undesired) turning of the rondel it is virtually impossible to select five cards at the beginning of a round of which you can be certain that you’ll be able to pay the required costs, irrespective of when and in which order you are forced to play them. |

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, there is little or no development in the game. Each round, the players are browsing their 15 cards to select their five candidates: there are too many possibilities, and all the different actions are represented so often and in so many different combinations on the character cards, that it is impossible to oversee everything. This autistic selection procedure is then followed by three repetitive rounds of playing and resolving cards, where weariness and frustration of the degree ‘clouds of steam out of your ears’ take alternating turns. Playing this game is therefore not a joyful experience.

© 2014 Barbara van Vugt

|

|

|

|

|

Die Glasstraße, Uwe Rosenberg, Feuerland Spiele, 2013 - 1 to 4 players, 12 years and up, 20 minutes per player

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|