Mystery of the Abbey

page 2

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confessional: the confessions of the last visitor still echo around: draw a suspect card from the last player that visited the confessional.

Chapter hall: here, revelations and accusations take place. You can accuse a suspect, or you can reveal a characteristic of the culprit (for example: he is a Franciscan, or: he has a beard). At the end of the game, players receive 2 points for a correct revelation and 4 points for a correct accusation, and they lose 1 point for a wrong revelation ,and 2 points for an unjust accusation.

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then the next player takes his turn. After four rounds, the mass ends. All players go to the chapel and pass on 1 to 6 suspect cards to their left neighbour. Then, the next mass starts. The game ends when the culprit is discovered. Not the person that accused the killer, but the player with most points wins the game.

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

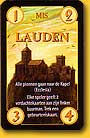

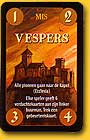

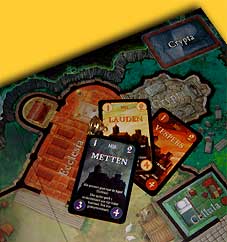

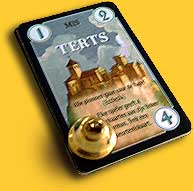

The Mystery of the Abbey is a beautiful game, with a colourful game board that still breaths the atmosphere of a medieval abbey, detailed miniatures as playing figures, a real bell to call people to the masses, nicely illustrated playing cards and a block with suspect sheets. The idea of the Masses is also clever.

Unfortunately, game play is not as good as its appearance. First, the game is very long: approximately two and a half to three hours. Second, it looks to be a conclusion game like ‘Clue’ and ‘Guess Who?’. But because players change cards so often one completely loses track within several turns, and the game is reduced to wild guessing, which is the main flaw of the game.

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A small example: a player asks Jack how many bearded monks he has. The answer is two. Next, Brian draws a card from Jack in his turn. Later that same mass another player asks Brian how many bearded monks he has: three. But did he just draw one of those from Jack, or did he already have three and did he draw a clean-shaven monk from Jack? Furthermore, as soon as the players pass on a number of cards to their left neighbour at the end of the mass, the chaos is complete. Therefore, it becomes impossible to ask useful questions, because the answer doesn’t give you any usable information. |

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Another drawback is that not the player that accuses the killer, but the player with most points wins the game. The correct accusation scores 4 points, but a revelation scores 2 points and the chances that you’re wrong are much smaller. The chance that the culprit is bearded is fifty percent, as is the chance that he is fat, but the chances that brother Jacob is the killer are of course much smaller. In addition, you can make as many revelations as you like, but you can correctly accuse the killer only once! |

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first two masses, when the number of cards that have changed owner is still limited are quite fun, and the game seems to be rather tactical at that time. But halfway the second mass and from then on it becomes tedious. Players are walking around the board, asking random questions, trying to obtain as many suspect cards as possible. Eventually you start asking all your fellow players if they have seen brother Jacob at some point during the game, hoping that this will bring you closer to discovering the identity of the killer. Of course this ‘strategy’ works eventually, but then it’s more a patience-game than a logic conclusion game. And that cannot have been the author’s intentions with this game.

© 2005 Barbara van Vugt |

Mystery of the Abbey, Bruno Faidutti & Serge Laget, Days of Wonder, 2004 - 3 to 6 players

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|