| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

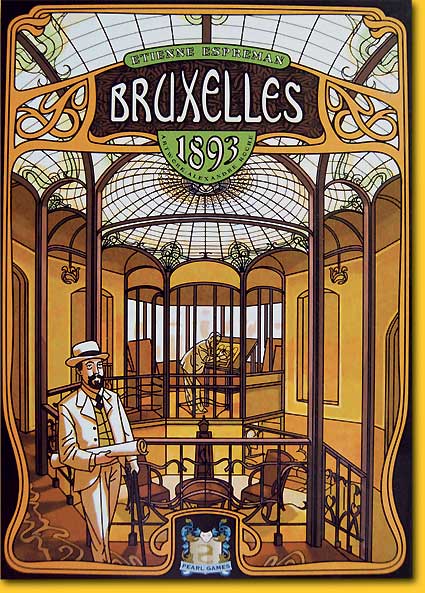

Let's talk about relations for a change: there are games that never will become your friend. This immediately sets the tone: Bruxelles 1893 is such an example. Why is one game pulled off the shelf faster than the other? The atmosphere of a game can be quite decisive, but also the quick retrieval of the gameplay. When choosing which game to play the first thought is 'How to play this game again?', the chances are high that the game will not be selected and will remain on the shelf. Yes, it all will come back when rereading the rules, but when a game has too many small rules in a rather abstract setting a player rather will prefer a game that has a smaller hurdle to take and that offers immediate play. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ofcourse not everyone has the same perception: for example, some will find the artwork beautiful and appropriate, while others see it as an obstacle for understanding the game. Bruxelles 1893 is praised by some for its beautiful and fitting art deco elements; others however just see two confusing and fussed game boards where sometimes one does not see the wood for the trees. Also there is the inclination to capture everything in symbols; this is executed ad absurdum when looking at the quasi game survey. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

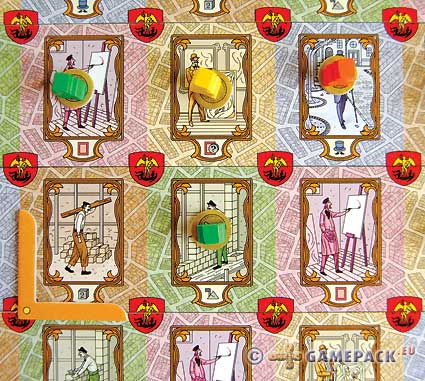

So the players are architects, but this feeling is not really felt in the game. Instead, players are mainly engaged collecting chips, money and cubes, and place their workers here and there to acquire art, sell it, buy a person card that supplies certain profits, take cubes or, indeed, and here we are for a short moment on track: to build a building, according to the rules in Jugendstil style but in fact represented rather abstract by a tile that is very replacable. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

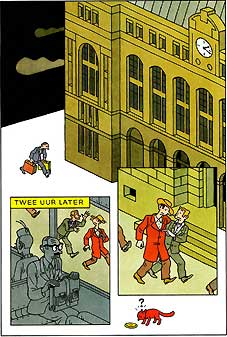

There are two game boards: a Brussels board and a Jugendstil/art nouveau board. Curiously enough the Brussels board has the most characteristics of Jugendstil, when looking at it with a benevolent eye; the Jugendstil board itself has more of an illustration according to the 'ligne claire/clear line' in the spirit of Hergé and Dutch illustrator and graphic designer Joost Swarte (wiki), the godfather of the term; anyway not quite Jugendstil. |

illustration Joost Swarte |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But there is more detail: the Jugendstil board cannot be played as such; each round a card is drawn and, according to the stated coordinates the playing surface is limited. Why, why is this hassle per se necessary? On the Jugendstil board players can acquire art; unfortunately they are not in charge and have to draw it from a blind stack. Each player who has more than one World Expo tile can draw that many art tiles and this way has a wider choice from the collection. Each of the five World Expo tiles goes to the player in a round who passes first. Default these tiles depict two 'Manneke Pis' symbols; there may be more on the to be earned bonus cards. The player with the most 'Manneke Pis' symbols will be the starting player for the next round. Great, this rule also is covered then! But: does it have to be so devious? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When art is sold, a grid on the Brussels board has to be consulted to determine how much money is earned as well as how many points a player scores. Somewhere in this grid there is a coloured marker that can be adjusted beforehand according to the amount of art tiles a player has in his possession. The art to be sold must have a different colour as the two pieces of art already in the window of the art store, otherwise there is no deal. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The card depicts a value; this is the amount that has to be paid at the end of the game, otherwise the player loses 5 points. Indispensable, isn't it, all this? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The action 'take resources' is a relief compared to this: take two resources, nothing more, done. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are some more actions on the Brussels board, from taking three white -wild card- resources, money, executing one of the five actions that are not available anymore on the Jugendstil board, or activating person cards already in possession of a player. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the end of a round again there is much to do: the player who has placed the most money in a column on the Jugenstil board may take the corresponding bonus card; the new starting player is determined, and players decide what they will do with their bonus cards: either use the symbol of the card, or place the card at their personal player board. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

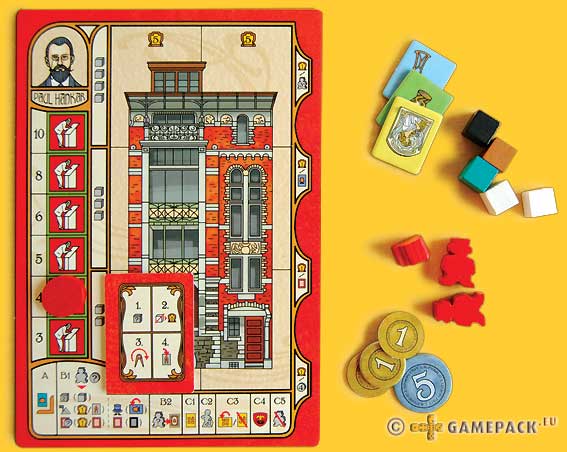

Here a player may choose from four different columns, each representing a category: for each 4 points as many points as there are point symbols in this column; and the same goes for each art work, person card or worker. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But we are not ready: at each symbol in between the columns on the Jugenstil board the player with the most adjacent workers scores as many points as his prestige at the Town Hall track on the Brussels board; a player advances on this list via the bonus cards. And finally the player who has placed the most workers on one of the four spaces of the Brussels board must send one to the justice department; these may return one by one via the bonus or person cards. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the end of the game the scores achieved so far are added with points for buildings, for bonus cards that players have placed at their personal board, for resources, and for the possession of the starting token. Person cards that cannot be paid for get a minus score of five each. Quite some mechanics, eh? Talking about relations: …Hello? …Where is everybody? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||